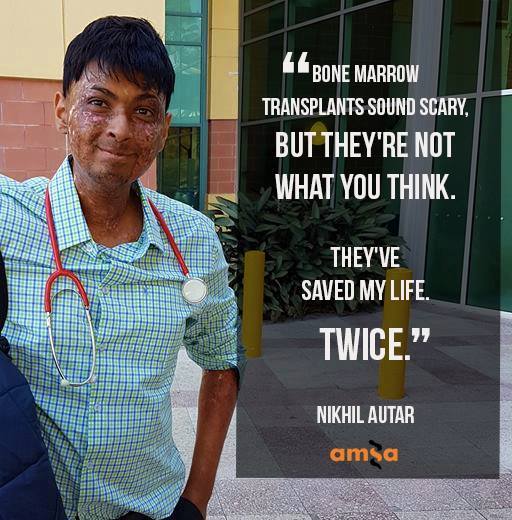

Bone Marrow Transplants are scary. And they’re a unique procedure whose impacts can last longer than many regular organ transplants. But they also save lives. I’ve had 2 myself. Both were allogeneic transplants, the focus of this blog post, which is where you receive your cells from a donor. I’m a medical student and tumor vaccine researcher, but I wrote this out to outline the process for a fellow patient recently – so it’s in plain English – and it’s also more patient focused. I found, personally, that a fellow patients’ words just stuck more. So I thought I’d share it with you. This isn’t medical advice, and every patient is different – so ASK YOUR DOCTORS ABOUT YOU! But it’s hopefully a mixture of reliable information + experience. I hope it helps. Feel free to reach out (there’s a contact button on the website – or messsage me on my Facebook page where I’m most active – or Instagram).

And sign up to my email list (I don’t post often, but you’ll be notified when I do this way!).

Bone Marrow Transplants

The bone marrow transplant procedure, in a nutshell, is basically getting someone else’s blood stem cells (haematopoiec stem cells is the technical name), located in their marrow, and infusing it into you, so it settles. They aim to get someone else’s immune cells in you, to kill off your cancer (your immune cells are made by your blood stem cells). And the major side effect, other than the dangerous infections you can get during the procedure and in the first 30 days due to, largely, chemo, is graft versus host disease, which can last a long time in others (but in small doses, is actually a good sign the process is working).

How it works for the donor – it’s taken peripherally from the arm, after getting a medicine which makes those stem cells enter your circulating blood for a few weeks (click here to learn about that).

On the recipient’s end, you receive it through an infusion into your veins, in most all cases. It eventually finds it way into your marrow and starts producing your donor’s blood cells (including white, immune cells), after a few weeks (it took 3 weeks for mine to engraft on both occasions, but it can vary).

The idea is, though you and your donor are matched as well as you can be – there will always be slight differences between you and them, which makes them recognise cancerous cells and kill them off, where your immune system may have lost the ability to do. This is a good thing in that it’s how the BMT or SCT (stem cell transplant) is supposed to work. But it also is the cause of the major side effect, graft versus host disease, where your donor’s cells attack your own organs. I’ll get to that later, here’s how it all goes though.

Prior to the transplant, you receive workup of some kind – often they want to ensure your underlying disease is under control. If it’s a blood cancer, often that will involve chemotherapy. Once they have the disease and any underlying conditions mostly under control, and they find a match, and coordinate timings (usually, you want to get the donor’s cells into you as soon as it’s taken from them), they begin the workup to the actual stem cell transplant process.

Usually, a week or so before, they’ll begin immunosuppressive regimens and chemotherapy that are designed to kill off your current immune cells. In younger patients, they may also offer total body irradiation, which is a high dose of radiation given to your entire body (in younger people, marrow can be produced all over the body, so all areas are targeted, though they will provide shielding to your brain and lungs, in most cases). The idea is to kill off your old bone marrow’s cells and replace them with your donors’.

I won’t lie, the BMT process and chemotherapy is tough. But it is lifesaving. Definitely listen to your doctors!

During the next few weeks, like many chemos, you will have a lot of your immune cells and your blood cells obliterated. So you’ll be very susceptible to infections. It is very important to do everything you can to avoid infections in this time, from limiting visitors (especially sick ones), to cleaning and bathing regularly (even when you won’t feel like it) and following your doctors’/nurses’ orders. You also may experience other side effects such as nausea, gut pain (from your stomach lining cells dying off), fatigue and general unwellness. There are many chemotherapy specific side effects too that may occur, and you may also get other side effects – eg. with TBI (total body irradiation), you often get mucositis – inflammation of your mouth and throat – which can be extremely painful. I’ve personally experienced this myself and highly recommend you follow doctors’ suggestions and get ENG tubes if they think it’s appropriate and helpful, and getting pain teams to come in and help too. Having said that – my second transplant was a ‘reduced intensity chemotherapy’ regimen. I only had nausea and didn’t get an infection once, and it went quite smoothly compared to the first. Everyone’s different, every regime is different, and even in one person, at different time points, you can react differently.

Other things they may do in your workup/the month before your transplant, is check your heart, and lungs, and, if you’re in that age category, your fertility. They’ll put a line in just before they begin treatment in hospital, this may be in your arms, or via ports they put into your neck. During the transplant, and the immediate transplant workup, they’ll watch over you, do bloods regularly, get scans when required, and treat things like infections. Infections are often the most dangerous thing you may face, but they’ll be sure to give you antibiotics, and other treatments, as required during this time frame.

This is the TBI – total body irradiation process. This is usually done in younger patients, as they are more likely to have marrow that persists in other bones of your body (adults often only have it in their sternum and hip bones). Hence why they shoot radiation at your entire body (left of this photo is a machine which does this). The rice bags keep you still and provide some protection to important organs like your brain and lungs. And they keep you still. It lasted 30 minutes, and I had 5 sessions over a week at a special clinic the week before my transplant). Straight after you may get a burning sensation in the skin (this is resolved by creame in most cases). The other common side effect is mucositis, a sore throat, which can be very painful. So listen to your doctors if they recommend a feeding tube! I learned that the hard way!

At some point, often 3 – 4 weeks after “Day 0,” where they infuse you with your donor’s cells, you’ll ‘engraft’ and have your donors’ cells start making cells in your blood. They’ll be monitoring for this. After this, a good number of people get acute graft versus host disease, which can affect any of your organs, and can be pretty severe. This occurs in the first 90 days usually, and can affect any of your organs – from your skin, to eyes, to liver, to gut. I personally had bad skin and liver and gut GVHD (in my first transplant, I had skin and liver aGVHD, and in the second, liver and gut aGVHD). Not everyone gets GVHD. It can be a good sign that you’re getting the ‘graft versus disease’ effect too (where your donor’s cells kill off/stop your cancer cells from returning), but too much GVHD can be bad too. Your doctors will treat you after you engraft with some medicines that suppress your immune system – often cyclosporine, but different doctors/patients use different treatments. If GVHD manifests and gets severe, they may add more or increase your dose. Or they may reduce them over time.

You’re still not out of the woods after this time frame. You can get infections, still. And with GVHD – days can be critical when it comes to your outcomes, so make sure you tell them of anything you may experience. With different organs, you may experience different signs. Eg – with the skin, you may get rashes or feel like your skin is burning. With the gut, you may get diarrhoea, sometimes constipation. With the eyes, you may get burning or find it difficult to open your eyes (which may be due to skin GVHD affecting the skin around your eyes). It varies from person to person. It’s VERY important you see your doctors if something happens. But sometimes, you won’t feel anything. With my liver graft versus host, I didn’t feel a thing, but had very very high liver enzyme tests.

I couldn’t find a clean, clear photo of my skin, so sorry for the captions. But this is chronic skin GVHD – I have quite severe chronic GVHD and it’s not too bad, other than the looks (I don’t mind the looks though – this is how I dealt with the social anxiety that comes to many post transplant, due to the change in looks). Acute skin GVHD can be more red and flared, and may occur anywhere. It may burn or itch. I know it’s hard, but try not to itch! But right now, as someone with chronic graft versus host disease, I can’t feel it, it isn’t painful, but it may make my skin less elastic, and does impede my joints a little bit. But I’m largely OK now!

Usually, they’ll tell you to come into hospital as soon as possible if you get a fever or infection symptoms of any kind. With COVID-19 going on right now, clarify with your doctors if or when to come in. Many hospitals, including mine, will give you a card to get you into ED faster. Even after the pandemic ends (which may not be for years officially), it may be wise to wear a mask and avoid crowded areas too.

Depending on your donor and your status, you may also get exposed to viruses that may put your graft (your transplanted cells) at risk. Your doctor will likely have you on prophylactic, preventative, antivirals, antibacterials, and maybe antivirals too to prevent this. And they’ll likely check your levels of various medicines, and monitor for these viruses too. This is why it’s really important to see your doctors and get your blood tests as much as they want you to. Hopefully, this will go from weekly appointments to fortnightly, to monthly, to 3 monthly, to yearly. And then comes long term monitoring.

You also generally feel tired. I did after both transplants for months. Some of the medications you may be put on have annoying or frustrating side effects – eg. prednisone is a steroid medication (not the muscle building type unfortunately), which can make you angry, make it hard to sleep, and make you gain weight. But it’s also lifesaving. It’s important to keep in touch with your doctors to monitor this.

The way cancer changed me used to really impact my mental health. To the point where, even though it was harmful for my health, I didn’t want to go out because of how it affected my looks. This is me years afterwards, but straight after chemo, on 100mg of prednisone, I had the classic “chipmunk face.” But I got over that after a while. This is how. I hope it helps those of you who may suffer from this out too.

After 3 months, you may also develop chronic graft versus host disease (cGVHD), which may manifest all over your body, and may get severe too. it’s important, once you get signs of anything weird, to tell your doctors about this so they can treat it, again. And treatment may last longer or be chronic, as the name implies. I still have some, 8 years out. But again, everyone’s different in this. I’ll make a post about this later – but there are many organs it can impact, from your skin, to eyes, to lungs and in rare cases, even heart. It’s important to get on top of this early. But the good news is, in many patients, it either ‘fizzles out’ or ‘plateuas.’ But without treatment, it can worsen, even after you’ve got it under control. So stay connected to your doctors and listen to their advice!

That’s the transplant process, in summary. I know it’s a lot of information. But the main thing, is it a marathon. But it is also curative – it was one of the first curative options we had for any cancer. Though it can be dangerous, it has a good chance of fixing many diseases. Your doctors wouldn’t be doing this to you if they didn’t think it could help.

I hope it makes sense. Let me know if you have any more questions. And sign up, do email me at info at nikhilautar dot (com) with any questions, and stay in touch!