Being a patient isn’t easy. Especially when you’re in hospital in an emergency situation, as I was last week… For those who didn’t know – I presented to emergency last week, midway through chemo, with shortness of breath and they ended up finding a new cancer on my fourth rib on the right. Don’t worry though – I’m fine!

They removed the lesion that was there and the worst case scenario – a relapse of my very aggressive original leukaemia has essentially been ruled out. Whatever the tumour is, that’ll likely be all that’s required in terms of treatment.

During that tumultuous week, my first where I’d gotten major surgery come to think of it, I probably met as many doctors as I had since being diagnosed 4 years ago. I definitely would have if you took out med students, interns and residents from the equation and just left the specialists. I met 12 anesthetists alone. By the time you’re reading this… I’d probably have met 14.

And over this last pressure-filled week, I’ve had some of the best and worst experiences with my doctors.

But let’s save the best for last…

I’d like to say, first off, these doctors I’ve been under – I don’t believe are bad doctors. Skill and knowledge wise, they’re far from deficient. Indeed, one is apparently one of the best in his field; one of three who even performs the surgery I needed last week in my nation. And they’re not horrible people either – I’ve come across worse, more abrasive doctors in my time, heard of many more horrible experiences, and circumstances. Rebukes from doctors and regular people to young cancer patients in particular commonly degrade patients. I probably came across these guys at bad times, in time-constrained circumstances or something of the like.

Luckily, I’m a person who can cope with that anxiety well. But not everyone can. So at the very least… for those doctors, future doctors, nurses or other healthcare staff reading on – this can serve as a lesson.

Words that were said to me, just last year. In truth, there were things out there that could, and indeed, have helped. Check out an entire album, asking what the best and worst things patients’ doctors have told them.

When I was told I had a lesion on my fourth rib – one that may be cancerous, as you can imagine, I wanted to see exactly what it was. Or at least learn more about it.

I was admitted to hospital on Tuesday morning, and found out about this lesion that afternoon. Immediately on hearing this, and learning that there was a spot in that same area last year – I wanted to see the scans or reports myself. I struggled (I was still cramping and short of breath) and limped my way to the nurses and doctors station and demanded to see my reports or my doctors as soon as possible.

After a while, the resident on my medical team walked in and told me the bad news. He confirmed that there was some kind of lesion, but when it came time to seeing the report… he couldn’t give it, as “Only a specialist could give such reports to patients, according to New South Wales Policy.” I was pissed. Angry,,, beyond words… They were my scans… my reports… about my body. Why was I not allowed to see them, and someone else was in the first place? Shouldn’t it be the other way around?

But I guess it wasn’t his fault. And I guess I could see a potential reason for such a policy. You wouldn’t want a patient to worry themselves too much, or be disclosed information without knowledgeable guidance…. Fair enough.

“Could you call or page my specialist so I could see them?”

No. That was for some reason or the other impossible too… He was probably scared of bothering him for this tiny thing. The systemic bullying, and even sexual harassment that come with the doctor hierarchy may have had something to do with this. If the consultant on call was such a bully, he may have had to cop a huge tongue-lashing from him, at the very least. Perhaps the laws were extremely restrictive. In any case, it wasn’t him I was angry at. I got where he was coming from, and saw that he had no power to change things here. So I tried everything; calling my own specialist on his line (he wasn’t in the office and couldn’t answer), calling my GP (who’s amazing and has helped me often in crisis situations in the past) and even calling and asking other doctors, including specialists at other hospitals, to see if there was something I could do.

Eventually, I resigned myself to waiting ’til tomorrow, for my consultants’ usual Wednesday “Grand Round”, where he and those under him would review all patients under their care for the report.

And the next morning, I got an absolute ‘Yes. Of course you can see your reports” from him.

That’s when I met annoying doctor number 1. The senior registrar (the level just under consultant) under my consultant was busy. I could understand that. She may have had a few long cases, or emergencies under her belt.

But for two whole days, two painstaking days of me asking her, the residents under her, my nurses, my doctors and my consultant again on the phone again and again, I didn’t get to see that report. I didn’t know for 2 days how large the lesion was. What caused them to suspect what they suspected it was. How much of my body would be deformed; cut away in this surgery that was being planned!

All I had to work off in this time were off remarks from my haematologist about a “lesion on the anterolateral aspect of the fourth rib” that radiologists suspected was a “chondrosarcoma” that the orthopedists (bone surgeons) recommended required me to go straight to “a rib resection” rather than a biopsy first. Words I could luckily grasp and understand, with my medical knowledge, but ones that would have left most other already anxious, suffering patients even more distressed.

Surgeons huh?

A shocking statement from a chronic illness patient, from a survey we conducted of chronic pain, cancer and chronic illness patients on patient-doctor relationships. Click here to check out the entire album.

Subscribe to my email list (don’t worry, I won’t spam you)!

[email-subscribers namefield=”YES” desc=”” group=”Public”]

When we asked her why the reports hadn’t been disclosed thus far, by anyone else, including the anaesthetists, orthopedists or the pain team who’d all been by by that point on her own rounds (which can happen at anytime in the day by the way – they often catch you when you least expect it, one after the other) later that day, she responded, brashly, dismissively even, to my obviously anxious mother, that “It’s because we’re the haem team.” before brushing on to the next question, failing to even acknowledge our plight.

After a rushed consultation (we were her last patient of the day, and we’d seen her laughing alongside colleagues later on; so she wasn’t rushed by other patients), a non-commital “Yeah, we’ll get on to it,” and a “hmph” and a small turn, she was out of the room, leaving us even more confused than when she entered.

The next day, early, before 7am (breakfast is served at absurdly early hours at St Vincent’s), we had more of the same. And it was only after cornering my haematology consultant onthe phone that we finally had the original resident, who’d initially been the one to refuse our seeing the reports, come in, show and explain the results of that CT scan to us. A mere hour before 5am Friday, the hour at which hospitals, for all intents and purposes, close.

Now I understand that doctors are busy. I understand that they don’t always have time, that they may have emergency situations and that they have a LOT of work to do. I understand that some patients are placed on higher priorities than others; indeed, rather than get angry, I’m a patient who’s grateful if he’s seen last, as that means I’m probably most well off, medically.

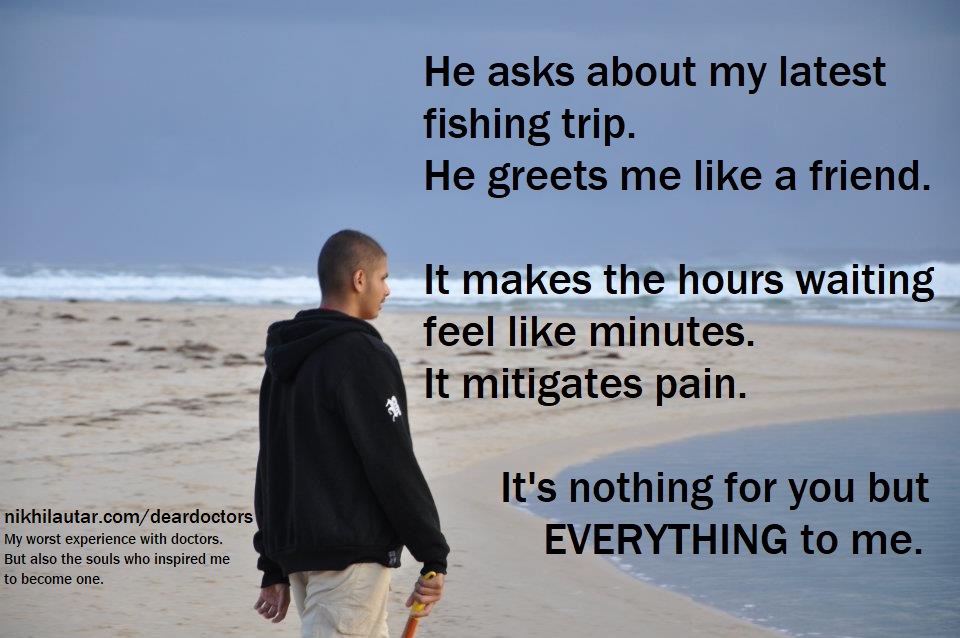

But though these things may seem like little, pestering requests peppering your busy schedules as doctors, they mean EVERYTHING to a patient going through tough times. Especially those newer to hospital experiences. But as you can probably gather… veterans like me get scared and anxious too. Even a quick explanation as to WHY you couldn’t get to me would have saved me heaps of pain.

The sad thing is, teams often have these informal priority lists assigned to patients to get procedures and scans during in-patient stays done, but the little requests, and sometimes even the less likely, yet all-too-possibly correct tests aren’t done. Because in addition to my not getting these reports, my echocardiogram (an ultrasound of the heart) was put to the back of the list so often, after they ruled out most of my major causes of shortness of breath, that it wasn’t even done until I specifically reminded the team about it. They’d simply forgotten.

The chances of there being a pericardial effusion causing that (they ultimately ended up pinning that initial shortness of breath that brought me in to my cramping as all the other tests came back negative) initial haggard breathing was unlikely, the chances of it being severe minimal considering my lack of the Beck’s triad of dangerous clinical signs. But it was still something that could have played a part in my initial presentation. Something that could have blown up in my face considering the fact I was getting major surgery in the chest later that week.

I understand there may not be time to answer everyone’s tiny little questions, or to grant every little request. I understand that there are days where you may be overwhelmed, where the concerns of a pushy family whose child has what’s likely a slightly cold seem irrelevant next to your failure to resuscitate a young man after an accident. I know you’re human, and can’t do everything…

But you don’t need to. Delegating the less necessary concerns, the less-likely-to-be-severe complaints of patients and their requests, to those below you in the medical team, those secretaries or clerks assigned to you, or to a colleague with more time on his hands is one way you can make the lives of both you and your patient better without impacting your own. If it does require a little effort on your behalf, then do document those “less urgent” concerns somewhere – maybe even design a symbol or mark to distinguish them from the rest of your notes – and try to get back to them later when you get a chance because believe me – it’s not just your patients who benefit from this – it’s you too. The small things can make the biggest difference to a patient going through what’s often the worst days of their lives, and if you can resolve those problems for people every ordinary day of your life… then your own life will be the richest of anyone’s in the world.

But by far the most human of these has been my opthalmologist; my eye doctor, and my first doctor, who’ll always have a special place in my heart.

That ophthalmologist though, she showed just how amazing she was in this last tumultuous week too.

Leave a Reply