So recently, a I was linked this article by many people. It’s been all over my Facebook feed, and I’ve been told to read it by many.

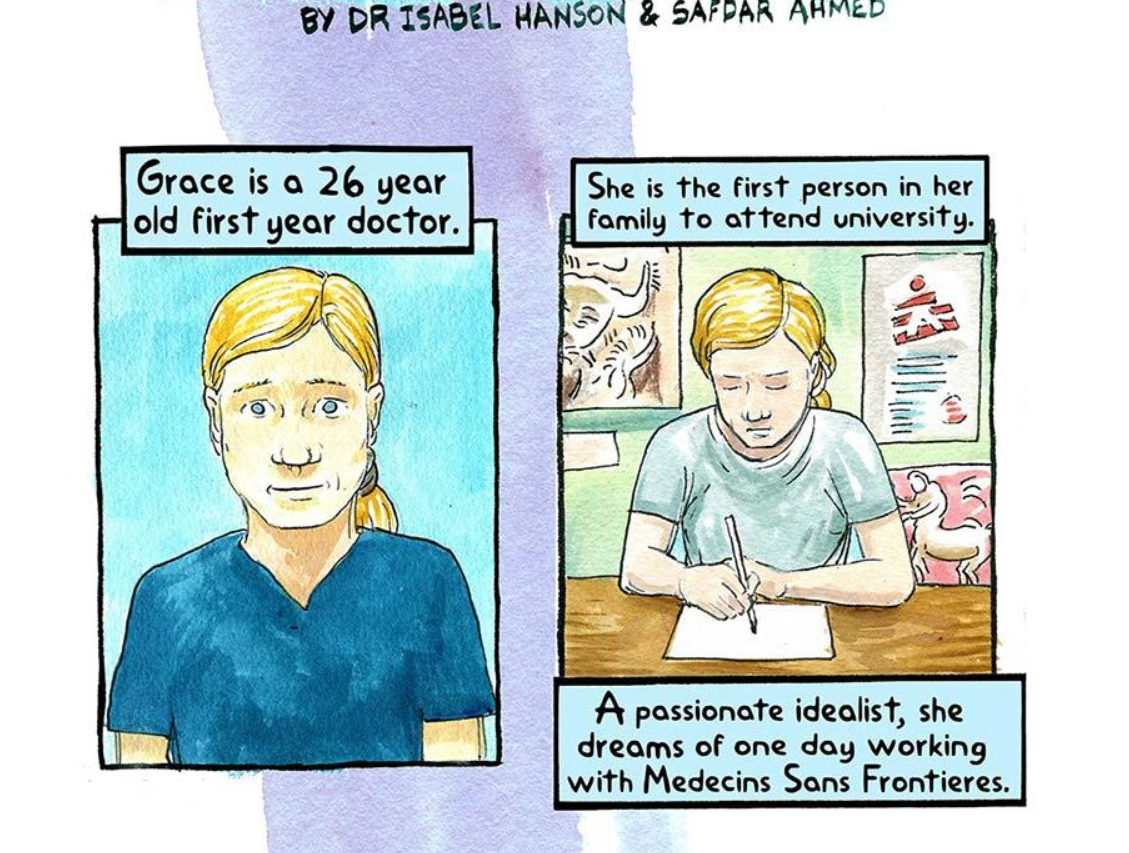

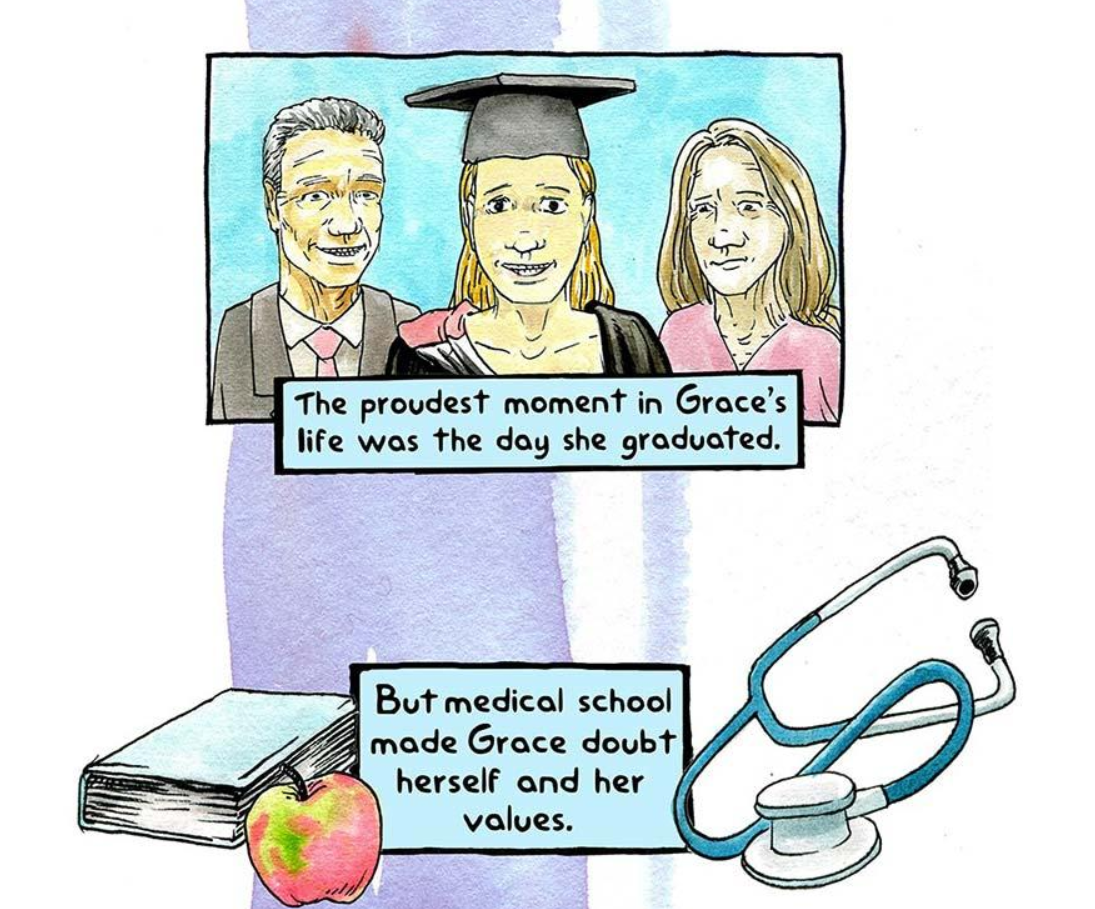

It’s really well done and articulates the challenges of hospital well. On both the doctor’s and patient’s side. It goes into the powerlessness patients feel, the confusion they face in hospitals, and the struggle of being a junior doctor in a system that’s pushed to its limits, and seems not to care. It features some really amazing artwork, and is told in the form of a cartoon, that really does capture your eye. As much as I may seem like I’m bagging on it now… it really is well done, and I highly recommend you give it a read.

photos and full article available at The Guardian.

But regarding the “novel” realisation that being a patient sucks…

A) No Shit.

Every 2 months a ‘profound’ article comes out after a doctor enters ED or faces his own health challenge and suddenly realizes – “holy crap I was treated like shit,” and i slapmy head. Hard (it’s probably why my memory sucks so much)…

You see it all the time in your patient’s eyes. It doesn’t take huge amounts of ’emotional intelligence’ to see that. You get used to it and start thinking “that’s just how it has to be.” and you are, quite reasonably, tired yourself, and often unable to do anything.

B) Where you can, instead of clapping your hands and crying ‘amen,’ go do something about it.

Take it from someone who knows… the tiny, little things which HARDLY takes time out of your day make a HUGE difference. When someone asks for pain meds, and they need it, chart it asap. And tell them, or get your nurses to tell them if it’s gonna take time, and explain why if it is going to take a while. “I haven’t got time right now, but I’m gonna try my best to get it to you asap” reduces suffering 90% compared to just being left hanging. Believe me, it does. Same goes for if you’re late, generally, in a clinic, or whatever.

Ask patients if they understand what you said when you chat to them, and if they have any questions. It’s not wasting time. It ensures that they buy into your treatment plan and comply with recovery, and they’ll trust you, divulge everything, and give better histories. If you’re too busy, let them know that you’ll get around to it when you can or to ask the nurses when they’re around next.

Asking about those little things like work, if they’re okay to get home, how they get their medications, is, for similar reasons, not a waste of time. And, importantly, they make you feel cared for.

The tiny things – greeting people warmly. Asking how they’ve been, talking about things important to them as you walk to your consult room… they are HUGE. My haematologist does that. There’s a reason why I drive, or take a train 1-1.5 hours each way to see him.

Because I feel CARED FOR.

That feeling is EVERYTHING. It’s your most powerful tool as a healer.

From someone who’s gone through enormous amounts of physical agony… trust me that I know what I’m talking about when I say that psychological/ emotional agony is 100x worse. And you ALWAYS have the power to change that. No matter what.

I get it. It feels hard to keep giving. Day in and day out, when you work such a stressful job and face failure on a constant basis… when you’re depressed and when everything feels even harder to do than normal… giving back becomes even harder. It seems futile. For many reasons – we doctors don’t take it as seriously as we should. Just going on and telling yourself you can’t do much is how we cope with it. But that’s the biggest trap of depression. Though playing the victim and focusing on the things that stop you is easier at the time, it really makes you feel shitter in the long run.

In truth though, doing the right thing – going “that extra mile”… it’s really as hard as it seems. The little things make just as much of a difference as huge, epic gestures. And ultimately, you being the good person I know 99% of doctors are underneath, wherever you can, helps YOU too. It reminds you why you got into this. It reminds you that you DO and CAN make a difference.

It isn’t that hard to do. And, like with anything in life, making the decision to give back where possible becomes habitual too. It becomes your norm. So anyone reading this… next time you’re out there… go that ‘extra’ foot or two. I guarantee you. It’s worth it.

This was a talk I did for the Australian Indian Medical Graduate Association’s annual general meeting a few years ago. I was quite raw… I’d just come from the funeral of an old friend and fellow medical student who’d taken his own life. I hope it helps those of you struggling out there, wondering, “what’s the point?” realise, that you can and always do make a difference.

Leave a Reply