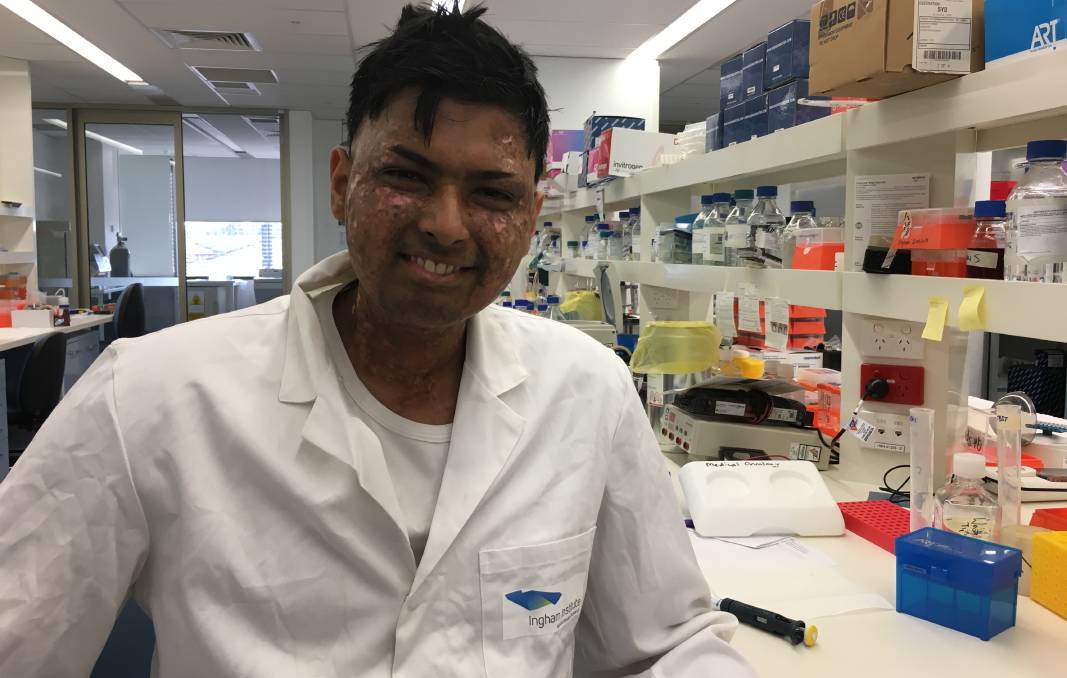

2 years ago, to this day, I received a bone marrow transplant.

It was the hardest thing I’ve gone through, as a cancer patient.

I spent weeks stuck in a bed, subsisting on unsolid food, barely drinking and in intense pain – even with morphine!

And for months after it, I was fed into a spin-cycle of maladies, starting with my skin feeling like it was burning for days on end without relief, followed by months of sickness and huge shifts in weight and ending with the a relapse and the knowledge that I’d have to go through it all again in my second transplant.

But it saved my life.

And I’m eternally grateful for it and for my donor.

One thing that may astound you is the fact that the transplant took only thirty minutes, didn’t involve any pain – it was just a minor, drip-like infusion!

Even DONATING bone marrow doesn’t mean having a needle put into your bones these days – at any point!

Bone marrow transplants are the cure to variety of illnesses – not just blood cancers/disorders which I speak about mainly on this post.

It has cured AIDs, which has only happened twice, EVER.

And it’s the only way possible for a mammal to change blood types.

Personally, I’ve had 3.

Click here to skip to a particular section of this post:

How it works

Finding a Match

How YOU can become a donor

What happens to the donor

What happens to the patient

How It Works:

So how does it work?

Basically, a bone marrow transplant, also known as a haematopoietic stem cell transplant, replaces your old bone marrow with someone else’s. You can also use your own cells for this, but for this post, I’ll only talk about allogeneic transplants, ones you get from other people, rather than autologous ones which you get from yourself.

Bone marrow is the soft, spongy tissue inside your bones which make your blood. It’s usually filled with haematopoietic stem cells – cells which rapidly divide over and over again and transform with the aid of certain hormones and chemical messengers produced by your body to eventually become your blood cells.

When a disease process affects these stem cells, they cause a malfunction in your blood cells which has a wide range of complications as your blood is responsible for delivering oxygen and nutrients to your body, and also your immunity, amongst other functions. If that disease involves a change in the actual DNA sequence of the stem cells and divide so it begins to take over the normal stem cells (in other words, if the disease is a cancer) and chemotherapy is not an effective cure for it, then a stem cell transplant can become the best curative option.

Now here, I wanna make it clear what I mean by “Bone marrow transplant” in this post. I’m referring specifically to Allogeneic bone marrow transplants – one received from SOMEONE ELSE. It’s possible to have an Autologous BMT too – in a procedure where your own blood stem cells are collected, so that they may be injected back into you after treatment. This is usually done to get very high doses, or treatments that would otherwise have killed off your vital bone marrow for good, into a patient, without killing them. The collected cells are stored and injected back into the patient after treatment has taken effect and remnants of the drugs have left the body.

What an allogeneic stem cell transplant does is get someone else’s bone marrow, blood producing cells into you. Not only does that allow for, if required, the same high doses of chemotherapy and other treatments to be given, it also gets someone else’s white cells (white cells are blood cells, made in the bone marrow) into you – their immune system. And this had the added effect of them attacking your cancer cells, where your old immune system couldn’t (often, cancers have special mechanisms by which they can evade your immune system), or of getting a new immune system in there to replace the old one.

The Procedure:

An allogeneic transplant involves, on the patient end, first, some chemotherapy and radiation to the entire body (blood production, though often limited to bigger bones like your sternum or hip bone in adults, can occur in any bone in the body) to ablate, or kill off, your old, diseased stem cells. Less intense chemotherapy regimes can also be given, in diseases with lower agressiveness or in patients who can’t take as much of a battering (my second transplant, due to all the drugs and radiation I’d had previously, was done using a “reduced intensity chemotherapy” regime. Many older patients are now able to get bone marrow transplants where they weren’t before due to these regimes).

The major side effect of this step is that your blood production halts, or stops outright, meaning you will be much more likely to bleed and bruise in that period and be very susceptible to infections – which are even more life threatening as you don’t have white cells to kill them off. Many of the drugs also have side effects of chemos (they often are chemos), and the radiation itself can cause severe mouth ulcers in some. This in itself makes the procedure very risky.

After this is accomplished, you inject your donor’s stem cells into your body in order to replace it. The donor’s stem cells take around 3 weeks to engraft, or take residence and begin working, in your bone marrow and from then on your donor’s stem cells become your own. Which means that from now on, you’re producing YOUR DONOR’S blood cells instead of your own.

The intent is not only for his (or your donor’s) cells to take over and start making proper blood cells again, but also to stop your old stem cells from coming back. You see, when his cells take over, his immune system does too. This is what is trying to be achieved in the whole procedure actually, a change in the immune system – as his immune system, being different to yours, will, hopefully, kill off any old stem cells of yours (including your cancerous ones) that remain. This is called the Graft Versus Disease effect (GVD).

The problem is, there is also a good chance that his immune system will also find your body’s other organs to be foreign to it and it will attack them too. This is called Graft Versus Host Disease (GVHD). And it is a big reason why it’s seen as even riskier than even chemotherapy and radiation.

In order to reduce the impacts of GVHD you are given some immunosuppresive drugs, which, as the name suggests, suppresses the immune system. When given early, it also prevents your old cells from coming back from the radiation and chemotherapy to cause rejection.

Examples of these are methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide, given before transplants to reduce both the risk of acute GVHD and the chances of your immune system from rejecting the donor’s stem cells, cyclosporine in the long term to manage chronic GVHD (GVHD that presents 6 months to years after a transplant) and prednisone, a corticosteroid, to manage acute GVHD (GVHD that presents after engraftment. Prednisone can also be given long term to manage cGVHD, and many of these drugs are used at different points).

GVHD can be life threatening, if not managed well. GVHD is a big reason why a transplant is seen as a very risky procedure. And though acute GVHD is more dangerous, chronic GVHD can have long impacts into the future.

But it’s not all bad news. Actually, the presence of GVHD and having a more severe version of it is correlated to a higher cure rate because the GVD will also be stronger. It’s a balancing act. You don’t want too much severe GVHD but a little bit is good as it indicates a good level of GVD (graft versus disease) as well.

And if you catch GVHD fast, and do as recommended by transplant hospitals, and rush to emergency, or call up your doctor immediately to initiate treatment in the critical periods (up to 3 months after a transplant, or when you feel classic symptoms of GVHD like fevers, gut pain/diarrhoea, skin prickling/redness/rashes or eye dryness. It can affect many other organs in different ways too) – it is often gotten on top of!

Finding a match:

When you’re being matched to your donor, it’s very preferable to have a complete HLA match. Basically your HLA is how your body recognises and differentiates your own cells from that of other foreign cells. You inherit your own ‘HLA settings’ from your parents, half from your mum and half from your dad and there are many HLA subtypes people can have, making it very unlikely for two random people to be matched to each-other.

Usually there are 6 main subtypes they look at when they’re trying to find a donor to match for you (they can go to 8 or 10 or more as well – I was a perfect 10/10 match for HLA with my donor). You have a 1/4 chance of any sibling being a match for you. In fact, transplants from siblings get lower amounts of GVHD, so they’re seen as less risky (by the way – even being a 10/10 will result in GVD and GVHD occuring, as there will always be little differences between your donor’s immune system and your own). But outside of your immediate siblings, the chances are very low due to the sheer number of possible HLA subtypes combinations that there are. But they do happen.

That’s where the bone marrow donor registries come in.

How you can become a bone marrow donor:

Bone marrow donor registries are usually done by country. It’s basically a huge database of people’s HLA combinations.

The process of actually joining the registry varies from country to country but NOT ONE involves too much pain! NOT ONCE will you have to get a sample taken from your bone marrow! What they need is a tissue typing test – a test which checks which HLA subtypes you happen to have.

In the United States, this involves simply buying a $5 test simply taking a swab of the inside of the your mouth and sending it away. In Australia, it involves a 20mL sample of blood, and has to be done while giving a blood donation (which takes less than 10 minutes and is no more painful than a blood test by the way) – and you have to ask and fill out a form in order to do it. This is done to ensure that everyone on the registry will be willing to actually give the donation. In the US a lot of people opt out of actually becoming a bone marrow donor in fear of the procedure, so finding a match doesn’t equate to finding a donor, which it usually does in countries using Australia’s approach.

With the help of my doctors, I was extremely lucky to find 5 matches, from around the world, and have had 2 bone marrow transplant from them.

Only 60% of people can find one.

So we need you to join up on the registry. Especially if you’re from an Asian or Indian or Middle Eastern background. It is more preferable to find someone who’s similar to you – whether it be by race, gender or age, and these races in particular have critically lower rates of people joining the registry.

Find out how, if you live in Australia, by clicking the link below:

http://www.abmdr.org.au/dynamic_menus.php?id=1&menuid=2…1

And if you live elsewhere, click here:

http://bethematch.org/Home.aspx

The procedure for the donor:

The actual procedure rarely ever actually requires harvesting of actual bone marrow either (95% of the time it doesn’t and a good portion of the other 5% choose to go through the surgery process because they have access to general anesthetic through that pathway). The donor has to go through a series of subcutaneous injections, small injections under the skin – usually into the belly or arm, of a hormone which increases the activity of stem cells and causes them to enter the blood more. From there, blood is collected from the donor from one arm, siphoned through a machine which separates the stem cells from the regular blood, and the regular blood is injected back into the patient’s other arm.

There is a chance that you’ll need to have surgery to remove actual bone marrow from your bones as well. Though it is unlikely nowadays, the procedure is done under general anesthetic meaning you won’t feel pain from the operation, and is very safe too.

The procedure for the patient:

The actual transplant is a bit of an anticlimax. The stem cells, collected in a bag, are infused into you, just like a saline drip, except with blood. In some cases, or in cases where a complete match wasn’t found, you can get a reaction to the actual cells.

What is dangerous during the procedure is the chemotherapy and radiation which kills off your original stem cells.

As with any systemic chemotherapy, your fast-growing cells are killed off. This includes not only your bone marrow, but also things like your hair and the lining of your gastro-intestinal tract. This leads to very low blood counts and hence tiredness, very low immunity and higher chances of bleeding, as well as abdominal pain and diarrhoea or constipation. There are a range of other side effects too such as nausea and taste changes which aren’t pleasant to say the least – but all of these can usually be controlled with medications.

The low immunity in particular is of huge concern. Your neutrophils, the white blood cells at the front-line when fighting infections, plummet to 0 and not only do you become more susceptible to infections, you also become very weak at fighting them. In fact, it’s the leading cause of death in not only bone marrow transplants, but also in chemotherapies and even in hospitals. Hence it is important to stay away from other people who may have infections during a transplant, and also important for appropriate hygiene measures to be taken, such as always sanitising your hands before allowing others (including doctors and nurses) to touch you and being placed in a room where the air is always being filtered.

Often, despite these measures, you can still get infections from your own body – it’s something you can’t help. These usually manifest as fevers or shakes or coughs and the like and are treated very aggressively, as your body has little to no capability of fighting them. Don’t worry though – medications can take the place of your immune system while it’s weakened – so infections are mostly controlled if caught early.

The total body irradiation is another factor which comes with a range of side effects. The procedure itself is a little daunting at first, involving being beamed with radiation for 20 minutes whilst being placed in a box and held still by rice bags, but after a few times (it’s done once a day on a 5-7 day cycle), you get used to it.

Again, it will cause your blood counts to drop and subsequently cause the cascade of side effects that come from that but it also causes skin irritation and in particular, mucusitis – or pain in your mouth and throat which, in my transplant, was the worse symptom. I found intense pain on swallowing – even if it was water or my own saliva and hence spent almost 3 weeks eating little more than less than a tub of gravy or custard and little sips of water. A morphine pump wouldn’t even help with the pain, and the sad thing is, 85% of patients who go through total body irradiation get this. But there’s a way around this too – a nasogastric tube which allows for food and water to be pumped into your body rather than forcing you to swallow it through a very sore throat.

There are also other ways of doing transplants which don’t involve the radiation aspect of it – and my second transplant is an example of it. It was a transplant whose pre-conditioning only involved chemotherapy(and that too a less intense variety of it) protocol known as RIC (Reduced Intensity Chemotherapy).

Bone marrow transplants are complicated, often risky procedures. They’re hard and often scary, and unfortunately necessary for some. But they give a second chance for people facing cancers, and other blood related or autoimmune diseases, at life.

I can never be thankful enough to my 2 donors for what they’ve given me – a total stranger – to them. And they haven’t asked for anything back from me.

They’re angels.

I hope for a day where no-one has to go through the things I went through during my bone marrow transplant. ‘Til that day comes though, be sure to join your country’s bone marrow registry and become an angel yourself.

To join the registry:

USA

Britain/UK: https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/british-bone-marrow-registry/how-can-i-help/

Australia: www.abmdr.org.au

Brazil: http://www2.inca.gov.br/wps/wcm/connect/orientacoes/site/home/informacoes_sobre_doacao_de_medula_ossea

Canada: https://blood.ca/en/stem-cell/onematch-information-new-registrants

India: http://mdrindia.org

Those from other nations (though this is aimed at professionals, you can search for your nation, and find organisations that have and contribute to registries there):

https://share.wmda.info/display/WMDAREG/Database;jsessionid=269E92F9EA24171227BF11FE71508EDA