This post is from the archives – my old blog where I go into detail a lot more – explaining an old treatment I had, called Extracorporeal photopheresis! Enjoy words from old me guys! Full details on how this fascinating treatment, and my experiences of it, are below (about halfway down!).

I’m starting a new therapy soon, called “extracorporeal photopheresis”, where they take huge amounts of my blood and expose it to UV light. It’s being done to to treat my Graft Versus Host Disease, a side effect of my stem cell donor’s cells being transplanted into me (caused by his immune system, which was put into me, thinking my skin, organs and body are foreign), which is why my skin is so scarred and I have slightly abnormal organ functioning.

It’s shown remarkable results. Nearly every patient with Graft Versus Host Disease (GVHD), be it acute or chronic, has shown not just improvement, but complete remission of skin hardening and scarring. It has good rates of resolving other organs affected by GVHD too, and the treatment itself has minimal side effects. Here’s a great little video on how it works.

A very good, easy to understand video on how it works!

But it still sucks that I have to do this.

Mainly ’cause I’ve had to have a catheter put into me. A plastic line, inserted into my jugular vein by tunneling through my chest, with 2 access points, or “pumps” hanging out. And though I know it feels normal after a week or so, it has already made me miss so many things.

An opportunity to help raise awareness about the importance and the impact of Youth Cancer on national TV, by driving a Ferrari (!) is just the tip of the iceberg. Luckily there were others to take my place, but I still missed out on being in a Ferrari Goddamnit!

The fact that I’ll be stuck in hospital, 5 hours at a time, two, or three days a week for the next 4 – 6 months, and that I won’t being allowed out in the sun for a day week this entire summer (due to exposure to UV light, manipulated in this procedure) makes it worse.

The fact that I missed out on attending the World Cancer Congress, where 8,000 leading researchers, doctors and health charity and organisations were going to discuss the latest developments in cancer research around the world torments me.

But the thing that gets me most, is that, yet again, I have to start all over again.

The whole year of exercise and work put into me getting back to my old self, culminating in me finishing a 200km bike ride… all poured down the drain.

A talk I gave to open that bike ride.

You’d think I’d be used to it now. I mean it’s happened so many times, right?

But every time it happens… it feels as if I’m being worn down, and each time it happens, I’m that much closer to giving up.

Despite me having such great support, despite my doctors’ assurances that I can still do some things, despite me having gone through this so many times before, I, like every other cancer patient, HATE that this thing STILL affects me SO. DAMN. MUCH.

But in the end, when I take a step back and think about it… I still know that I have a choice in all this.

I still know that though this sucks… I wouldn’t be getting this if they didn’t think it’d help.

And when I take that step back and look at the big picture; the fact that this treatment may just stop my steroids, my cramping and the constant itching in my skin… I realise that in truth, I should be celebrating this.

When I look at why I’m most put down by everything cancer’s done to me; that these constant treatments and these side effects are stopping me from being the old me… I get angry.

Because though I’m sick of the effects cancer has on my life… I’m sicker of the fact that I keep making myself feel bad because of it.

I REFUSE to lament that I’m limited to a “new normal” after cancer. Because the ill effects of cancer, they don’t define me… they shouldn’t make me detest myself…

The fact that I still manage to function, that I still manage to find reasons to smile despite all this, and that somehow, despite all this, I’m STILL able to learn from this should be something to PROUD of.

Too often we cancer patients, we trauma and depression victims and we who have “missed out” on our dreams are told to accept our “new normal”. As if what’s happened, limits us.

But though we may have had much taken away from us… we can still be us, we can still be happy, and we can still GROW despite it all.

Yeah, this, and other treatments, may physically stop me from doing things in the future.

Indeed, when I think about it, this may just be the golden opportunity, the extra few hours in my day that’ll allow me to focus on other, more important things.

Writing my books.

Learning more about cancer, depression and global inequity that I may help more people in the long run.

And just being happy for being me, instead of what I can do.

I’m gonna make the most of this. And I hope this helps you make the most of yourselves too…

**********************************************************************************

This bit is for patients or medical students, or those interested in this treatment I’m going through and learning more about extracorporeal photopheresis.

What is Extracorporeal Photopheresis? And how does it work?

Well, basically what happens is they take blood out of your body (hence “extra” – or out of, “corporeal” body) and put it through a machine that exposes the blood to UV light (hence photopheresis – “photo” being the UV light and “esis” being blood put through a machine or filter).

The same video as above, but it’s a really good summary, which is why I’ve linked it.

They need good access to some large veins to get a lot of blood through the machine and gain maximum benefits from the therapy, which is why they usually make sure people have VasCaths or other catheters in to ensure access to veins before doing it. Though some people have good enough veins to do it without it, often, due to the sheer number of times they need to access it, they can start to fail half-way through, and the tunneled (under the skin) ‘Vascath’ port ends up being the less painful, less intrusive option.).

(by the way – while you’re reading this, be sure to subscribe to my email list if you wanna keep hearing about my journey and other cool stuff in medicine!).

[email-subscribers namefield=”YES” desc=”” group=”Public”]

The whole process works by killing off T-cells, a type of immune cell which finds things that may endanger the body and attacks them, and activates the immune system, that have been activated and are on the attack or that are abnormal.

These cells are responsible for graft versus host disease, an autoimmune process that’s often felt by bone marrow transplant patients. It occurs because the donor’s bone marrow stem cells (bone marrow contains haematopoeic (blood) stem cells, which produce white cells, which are a huge part of your immune system) is slightly different to your own cells. Even though you are tissue matched to your donor, there will always be slight differences between you and someone else, hence the T-cells attack your body thinking it’s a foreign particle of some kind, even though it’s not.

UV light, in combination with psoralen (8-mop or methoxypsoralen), a medication which sensitizes your cells to UV light, has been shown to kill mainly activated or abnormal T cells. The ones that are attacking you or causing you problem, fits this bill.

You’re essentially given the medication, and then a procedure where blood is collected from one arm and put back into another (or through the port), with your immune cells separated out. These immune cells are exposed to UV light (inside these very expensive, specialised machines) and then injected into your body.

The blood from your entire body doesn’t pass through the UV-light machine though. It’d be very hard to ensure it all does.

So there must be a systemic mechanism of its working here too – a way for the 10% of your blood that is passed through the machine, to cause an effect on the rest of your immune cells.

The activated or weird T-cells aren’t just all killed off, the treatment has to somehow cause the stopping of the production, or else the killing off of the immune cells causing the graft versus host disease.

And though it’s not set in stone, or observable right now, this is how we think it works (remember, there’s a disclaimer on the side of this here for a reason! Always ask your doctors if something is right for you!)

The T-cells that are “killed off” by UV light induce apoptosis, or self destruction, of the cell. And when these dying T cells reenter the body, they are taken up by macrophages and dendrites and other “antigen-presenting” or immune system stimulating cells, that likely cause your good immune cells to recognise the bad ones as foreign. This causes an immune response when self-reactive T cells are produced, and continues to get better over time as your body forms immunological memory cells which stop graft-versus-host-disease cells from coming back. This is combined with other likely factors in play as well.

So that’s how it works.

How effective is it?

In patients who have failed steroid and other immunosuppressing therapies in reducing chronic GVHD, ECP was remarkably effective. Rates of 80% – 100% cessation of skin GVHD are noted. With those with other forms of GVHD, like liver, gut and eye GVHD, high rates (70% and up) were noted in those who started it early after GVHD had set in (about half a year after it had started). However, lower rates of success in other organs were seen in those started later (1.5years median), and lung GVHD seems to have low rates of response to it in one study, though others suggest a decent rate.

These studies were done on those with severe, uncontrollable chronic GVHD, might I add, so success rates may be slightly better.

And many of the studies done on this are rudimentary. There are different protocols with different measures of effectiveness. But the best sources for this (the ones I got my data from) are below:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3766348/

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25025011

So what does it involve for the patient?

Well, first off, there are many protocols around the world for this, as stated above, and so the length and time involved varies.

In my case, I’ll end up getting 25 treatments of this, usually 2 per week (so around 3 – 4 months), plus any extra time I may need to show full response. I know at MD Andrerson, one of the world’s largest blood cancer centres, that they usually continue treatment for 6 months.

In most cases, it takes about 4 – 6 treatments (nurses say 2 – 3 months usually) for the effects to start showing.

Before you start, you put in the VasCath or other means of venous access. As I said above, you can avoid this, but it’s not recommended.

Each actual treatment will take about 3 – 4 hours on the machine. It is a long time, and the machine can be a little noisy, and there may be small side effects such as a mild fever, slightly lowered blood pressure or cramping, but these usually die down after the first few treatments. Blood will be taken from your VasCath and pushed through the machine, and pumped back into you simultaneously. I’ll update this while I’m having it to let you know any other thigns you may feel.

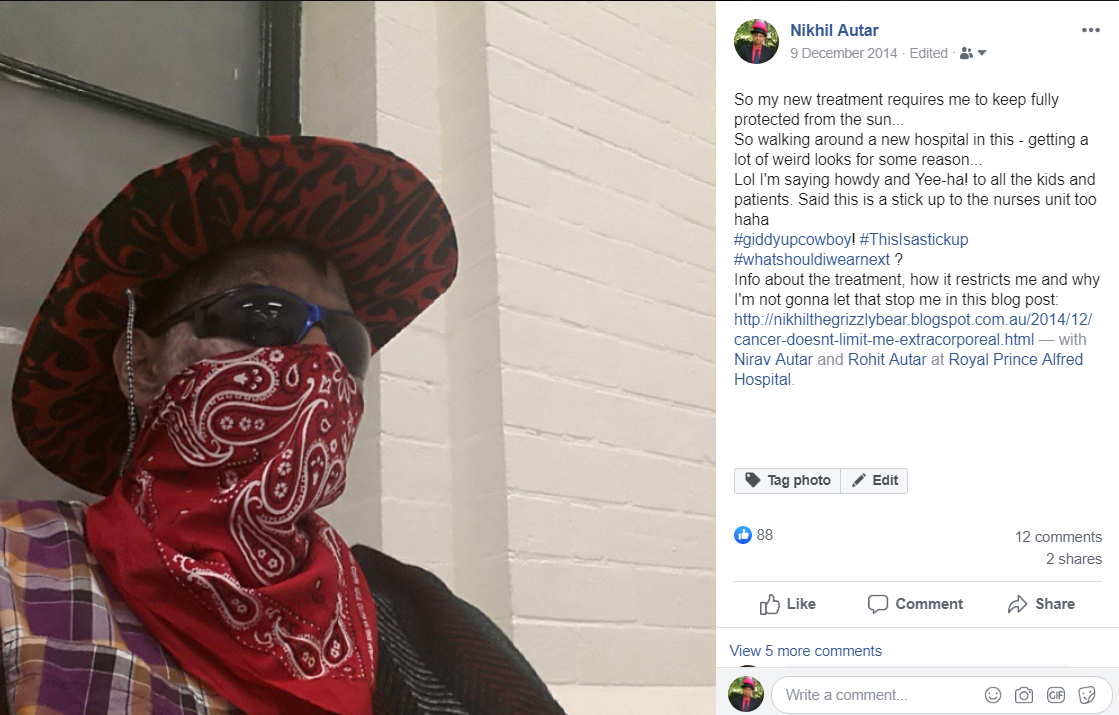

And after it, because you take a medication called psoralen, which sensitizes your body to UV light, you’re required to stay out of the sun (or wear large covering clothing) and to wear sunglasses for 24 hours after each treatment (the glasses, they recommend, to do it inside) to protect you from burning and lasting eye damage.

My experiences of it – 35 treatments in!

Part 1 )the first time it happened. This is part 2 (last week’s)

Leave a Reply